Consciousness in the Aesthetic Imagination

The real voyage of discovery does not consist in looking for new landscapes, but in seeing with new eyes.

—Marcel Proust

Sunflower Events

What can art tell us about the nature of consciousness? The question is meaningless if it refers to the personal convictions of this or that poet or musician, this or that genre, school, or movement. The goal of this essay is to explore what the things artists make—the works of art themselves—tell us about the nature of mind and matter, self and world, over and above their creators’ personal beliefs. Is there a metaphysics that art as such implies? Or maybe the question is better framed in McLuhanian terms: What is the message of the medium of art with regard to the nature of consciousness?

The first thing that strikes me is that art is not discursive. It doesn’t constitute an attempt to represent things—to talk or think about them. Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings isn’t a piece of music about sadness. It is a sadness in itself. It is a sadness that has acquired a form outside the private experience of a subjective mind. If after the death of the last living thing on earth, there remained a radio playing the Adagio over and over again among the ashes of civilization, there would still be sadness in the world.

Works of art like Barber’s famous composition do not represent but enact the movements of experience. By doing this, they preserve these movements in material form. Only poor art tries to represent or reproduce, and that is why it generates only clichés, stereotypes, and opinions. Genuine art isn’t representational but demonstrational and imitative. It is deeply implicated in the experiential dimension, all that we associate with consciousness. But whereas most of the time we approach consciousness discursively from an assumed outside perspective, works of art catch it from within, in media res. What art gives us is consciousness in action—not consciousness of the world, but consciousness in the world.

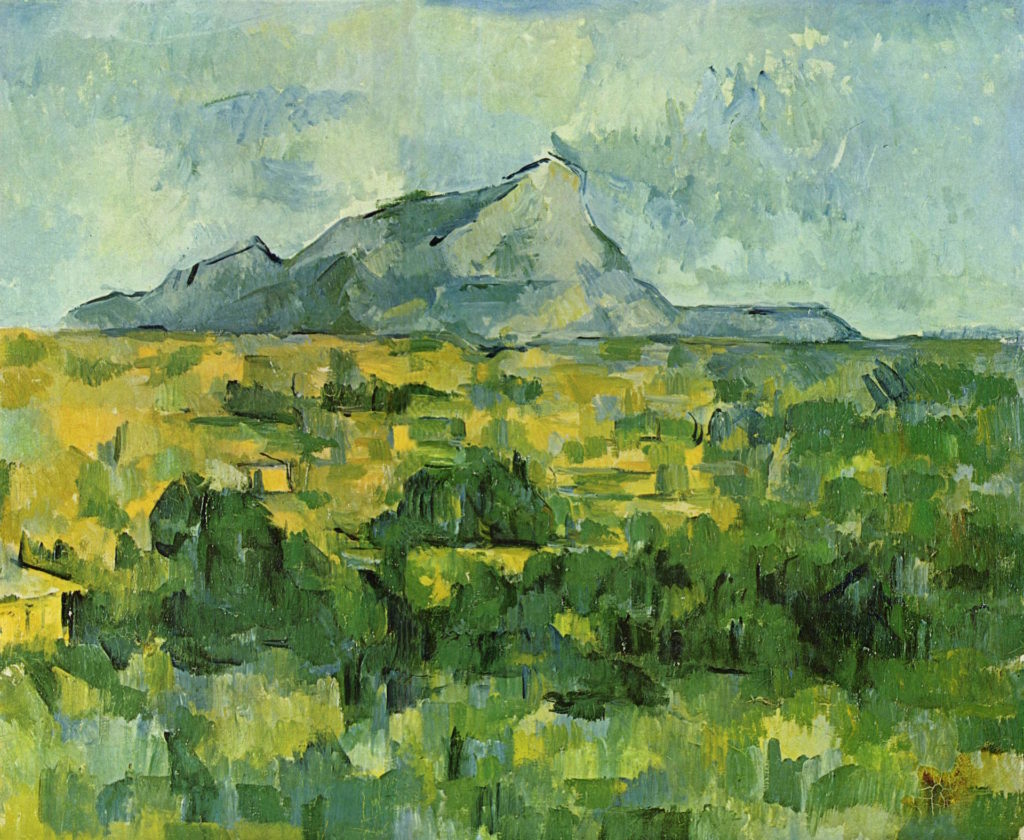

In Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice, I try to show this by comparing a technical drawing of a sunflower found in a botanical guide with one of Van Gogh’s sunflower paintings. The technical drawing as such makes no claim to art beyond a broad, utilitarian sense of the term. It has a diagrammatic function. Its goal is to communicate the concept “sunflower,” helianthus annuus, outside of any particular instance of the species. What we are given in this image is the sunflower as an ideal construct, the quintessential sunflower of which every physical specimen is a more or less exact copy.

Van Gogh, in contrast, captures the sunflower as an experience, a singular encounter. The resulting image exudes a presence that is like an alien sentience. Sunflowers are no longer instances of a type but sui generis. Each is a unique and unrepeatable event in reality’s unfolding. It’s only after the fact, when the intellect steps in to take apart the experience, that we label the image “sunflowers in a vase.” If the botanical drawing suggests something like Plato’s metaphysics of ideal forms, the painting throws us back to the likes of Heraclitus, the Pre-Socratic philosopher who held that there is no fixity of being, only a flux of becoming.

In Van Gogh’s work, something familiar is reimaged in light of an ineffable newness that inhabits it and makes it an event. We realize that there is no such thing as sunflowers in the abstract, but only these sunflower-events that the intellect then classifies according to generalities which exist only in and for it. The way I put it in Reclaiming Art is that, while the botanical drawing eliminates every anomaly in order to represent the generic specimen, the painting removes all that is general in order to preserve only the anomaly. That’s why even the most naturalistic work of art contains a note of strangeness, a soupçon of the Weird.

Art isn’t concerned with how the world appears to the intellect because it operates at the level of sensations as opposed to concepts. The term “aesthetic” denotes an engagement with reality at the pre-conceptual level of instinct and intuition, affect and vision. Van Gogh’s picture conveys its sunflowers as pure sensations, that is, as that which exists before the intellect subsumes it in a generalization.

Sensations are the immediate data of consciousness. Before the intellect reorganizes it according to general ideas, reality is a sensuous affair through and through. That’s why it isn’t wrong to speak of aesthetic experience as unmediated. There is always a moment, before the intellect does its thing, during which reality reveals itself to us directly. Something exists before we name it, before we attribute a function to it, before we subordinate it to our ideas, beliefs, and judgments—before “we” come into play at all as rational subjects. This is what I call the Real. It isn’t generic reality but the raw Real that comes to us in works of art.A Play of Forces

Nothing in the foregoing implies that the aesthetic imagination is opposed to intellect. Novels, poems, films, paintings, and even choreographies are full of general ideas and concepts. But when such things appear in an artwork, they do so as sensuous events within the aesthetic world that the work evokes. They are on a plane with everything else, because the intellect too is in the Real.

Take for instance the idea of Christianity in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. What is it that makes this novel, written by a fervent Christian, different from those fundamentalist paperbacks we find on drugstore bookracks? It’s that The Brothers Karamazov doesn’t absolutize Christianity. It doesn’t raise Christianity above the fictional universe in order to make it a given on which the significance of other things depends. On the contrary, Dostoevsky allows his Christian faith to exist on a plane with the other forces that make up his universe.

At the sensuous level of aesthetic vision, all things—even ideas, concepts, opinions and beliefs—manifest as forces. In philosophy, it was Friedrich Nietzsche (and Baruch Spinoza before him) who showed that even the most abstract concepts are, at bottom, feelings in disguise. At any rate, this is how they appear to the aesthetic imagination. Concepts have no transcendent power over reality. They don’t hover above the spatiotemporal universe, shining down upon it. They are no more (nor less) “objective” than anything else. Like all things, concepts are events in a world. You use them as you’d use a hammer, to build something up or tear something down. Even the loftiest conceptual system fully belongs to this world. Judging by the novels he wrote, Dostoevsky didn’t conceive of Christianity as a theory to be accepted as true or rejected as false. He saw it as a force that inhabits us, opening up new possibilities and closing off others. A similar view runs through the work of Nietzsche, who was above all a great aesthetic thinker, maybe the greatest who ever lived. And Nietzsche’s key insight is that the world is shaped by a primal energy of desire. Look at any concept or idea closely enough, he says, and you’ll see that within it there burns a sensuous force, a “will-to-power.”

A scene from Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. Illustration by Alice Neel for a never-published edition, 1930s.

Aesthetic vision apprehends the universe as an immanent field of living forces. All of reality is ensouled, willful, alive. Small wonder, then, that works of art present the world as innately sentient. The forces that compose the aesthetic worlds of a writer, filmmaker, or painter are not the blind and brute entities of physics. They are forces of desire, or what John Carpenter, in his brilliant film Big Trouble in Little China, refers to as “furies.” Any painting or piece of music could serve as an example. The colors and lines that make up a painting, like the notes and sounds that make up a symphony, are more than the isolable elements they appear to be for the intellect that breaks the work down to its constituents. They are interdependent furies vying with one another, forming alliances or waging war to produce what is called a composition. The same is true of other art forms.

Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there. [1]

When Chekhov advises writers to remove extraneous details from their narrative work, he means that every element should enter into a dynamic relation with every other element as well as with the work as a whole. This is because each one is itself an intentional force that alters the world of which it is part. The rifle on the wall isn’t just a rifle on a wall; it’s a will, an intention, a desire that at some point must fulfill itself. In art, guns want to go off. This is the case not just with inanimate objects but also with with places, settings. Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining presents the Overlook Hotel as a living creature with at least as much agency as the hapless family trapped inside it. Likewise, in Dickens’ Great Expectations, the dank and foggy marshes of Kent, Miss Havisham’s rambling house, and the city of London all exert a presence that makes them more than mere backdrops for the actions of human figures. As a matter of fact, in the work of both Kubrick and Dickens, human characters are themselves the expressions of places which are every bit as alive and ensouled as they are, sometimes even more so.

Artists are people who can experience the world imaginally at the level of sensations or aesthetic forces. Matter for them is alive and vibrant. Through their eyes, life in its broadest sense leaves the domain of biological entities to become an energy coursing through all things. And by “all things” I don’t mean static objects but events, becomings, each relating to every other. The aesthetic imagination sees the world as a clash of forces, an agon radiating a strange vitality which defines the Real. “Art,” wrote the American philosopher Susanne Langer, “is the objectification of feeling and the subjectification of nature.” In it, all that the human intellect normally claims as its exclusive property is restored to the forces that compose a pre-human imaginal world. All that ordinary awareness deems to be mere objects is also restored to those forces. There is only the agon, the Event that is a kind of miracle occurring at each moment. Art captures the moment to preserve the miracle.

The Transcendental Field

Under the terms of ordinary subject-object awareness, the experience of, say, a vase of sunflowers “belongs” to us, in the sense that we are the basis on which such an experience can be said to exist. But when Van Gogh perceives a vase of sunflowers, he experiences it as belonging to something bigger than his subjective mind. This “something” is what Jean-Paul Sartre called a transcendental field, a kind of proto-consciousness in which beings arise as subjects and objects.

Deleuze defined the transcendental field as “a pre-reflexive impersonal consciousness, a qualitative duration of consciousness without a self.” [2] It is this field that produces Van Gogh as a subject and the sunflowers as an object at one and the same time. Subject and object are the two poles of an unprecedented event. The painting is an embodiment of the event, embracing both the experience and the act of experiencing.

The transcendental field isn’t projected by a conscious mind. It is the impersonal locus from which conscious minds emerge. Because Van Gogh stayed true to the field, allowing his self to fold back into the event instead of insisting that the event was happening for him, he produced a work no one can dismiss as just another object. The painting is alive, the sunflowers too. The life and agency we would normally ascribe only to the human mind is present in them. We can’t in good faith continue to say that the sunflowers are just “contents” of “our” perception, at least not unless we also admit that we are contents of their perception, since the sunflowers here are creatures in their own right, watching us watch them. This, I think, is what Paul Cézanne was getting at when he said that in the heat of creation, he and the landscape he painted formed a single “iridescent chaos.”

The subject-object structure that the usual conception of consciousness assumes doesn’t obtain at the aesthetic level. Normally, when we talk about consciousness we mean mind, personal awareness, self-consciousness, the “I” that knows itself aware. But as every psychologist knows, subjectivity represents only a very small part of psychic reality. We would do well here to consider one of the key insights of Sartre’s seminal essay, The Transcendence of the Ego (1936):

When I run after a streetcar, when I look at the time, when I am absorbed in contemplating a portrait, there is no I. (…) In fact, I am then plunged into the world of objects; it is they which constitute the unity of my consciousness; it is they which present themselves with values, with attractive and repellant qualities—but me, I have disappeared; I have annihilated myself. There is no place for me on this level. And this is not a matter of chance, due to a momentary lapse of attention, but happens because of the very structure of consciousness. [3]

I wonder what Sartre would have said on the subject of the neurological condition known as blindsight. People who suffer from blindsight are cortically blind, but able to respond to visual stimuli as though they could see. For instance, a person with blindsight will report being unable to see anything when a red handkerchief is dangled in front of them. Nevertheless, when asked to name the color of the item they will answer correctly, “red.” Blindsight is consciousness without awareness, perception without sight. It takes the “con” out of consciousness to confront us with a more primordial sentience that is completely objective.

Which is to say that psyche can be uncoupled from subjectivity. C.G. Jung was right to describe his collective unconscious as an objective psyche: it is the weird sentience of a transcendental field, “a qualitative duration of consciousness without a self,” an unconscious that isn’t a repository for static archetypes but the energistic field of Nature understood as an eminently creative and dynamic process. Cézanne’s iridescent chaos is a perceiving chaos. It is in some strange way alive: it sees, thinks, and desires. Nietzsche’s utterance, “And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you,” has more than metaphorical value.

When we imagine that it is the forces shaping the universe that perceive and not the subjective minds that are born and die inside this universe, we are close to the imaginal vision conveyed in art. As a metaphysics it amounts to a form of animism or panpsychism. The panpsychic universe is one that exists in itself, objectively, just like the material cosmos of scientists, but whose molecular sentience produces minds all over the place. Experience or perception is not the cause of existence, but its perpetual correlate. To be is to perceive.

Everything is Alive

Matter is physical, matter is psychic: both statements are true when made in unison. As soon as one is used to negate the other, however, the aesthetic vision is lost. For then concepts are placed above the sensations that shape them, the intellect is raised above Nature, and we are inevitably left with some form of anthropocentrism. The panpsychism of art, by contrast, entails that human consciousness is just one manifestation of a sentience that precedes human intellection. The Real ceases to be the comfortable theatre for human action it is for idealists and the hostile no-where it is for materialists. It is very much our home, but our home is a haunted house: strange, uncanny or, to borrow a word from weird literature, eldritch. Eugene Thacker, in a probing analysis of Fritz Leiber’s story “The Black Gondolier,” describes a moment where “everything human is revealed to be only one instance of the unhuman.” [4]

The above image by the great Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi contains a couple of empty rooms in a turn-of-the-century flat in Copenhagen. There are no human subjects in these rooms. The feeling of emptiness is reinforced by the mirror, which reflects nobody. Yet somehow, sentience isn’t absent from the image. There is a haunting presence here, immanent to the place itself. The rooms exhibit what J. G. Ballard called a “transcendental geometry,” intimating a non-human life that thrives even in the most humanized spaces. We’ve all experienced it before, be it in an empty hotel corridor, an old house, the depths of a forest, or some derelict urban area: a presence that precedes and exceeds us, that perceives us even as we perceive it, a strange form of life irreducible to our own minds, but pointing instead to an alien knowing underneath the familiar world. There is nothing cozy about this presence; indeed at times it verges on the frightening. Facing it means confronting the “it” that shapes all things, even the most familiar ones, even a couple of empty rooms, even the eyes, brain, and spinal cord with which I perceive those empty rooms.

Hammershøi here gives us a glimpse of this occluded reality. When we allow ourselves to enter into his painting, there is a chance that it also enters us. Who hasn’t experienced a film, play, or concert so powerful that for hours or even days afterwards it seemed to refashion the world in its image? We are all poets when this happens, seers beyond the ambit of a closed, all-too-human subjectivity. What disappears in such moments of encounter is the judgment underlying the view that humans are the centre of cosmic attention. Philosophically, these moments challenge any conception of consciousness which, construing the world in terms of representations for human beings, reduces the teeming forces of the cosmos to the props and decor of an all-too-human stage.

The notion of consciousness implies two things: a spatiotemporal perspective, and a power to choose among potential actions or thoughts from this perspective. As Henri Bergson argues in Matter and Memory (1896), to be conscious means to be able to discern. My consciousness is my freedom to direct my becoming as a being in a world of beings. Consciousness, at bottom, is discernment. But what is the difference between discernment proper and the judgment referred to above? Simply, there is discernment when I act with the awareness that my perceptions and thoughts are contingent and relative. Given a different set of circumstances or a new perspective, I would perceive and think differently. This is consciousness in the world, consciousness as a field in which my I and the objects it apprehends arise on the same plane.

Conversely, there is judgment when I act under the belief that my perspective is necessary and absolute; that is, when I assume that my perspective is the one from which final statements can be made. Explicitly or implicitly, this is what happens whenever the subject is posited as the source of consciousness, whenever experience is attributed to a pre-existing experiencer, in short, whenever subjectivity is located outside the phenomenal world. Discernment supposes in an open reality; judgment, a closed one. I judge when I decide that consciousness begins with me or my group, that objects exist only in correlation with me or my group, when I choose to perceive the ever-shifting horizon of my human perspective as the absolute horizon of reality itself.

An Allegory

Oscar Wilde famously wrote, “All art is quite useless.” What he meant, I think, is that the aesthetic nature of the work of art allows us to feel the ultimate “uselessness” of all things. It connects us to what the Buddhists call sunyata, emptiness or openness. Art makes us see things for what they are in themselves instead of limiting them to the uses we normally put them to. To see the world aesthetically is to see beyond the judgments of self, culture, and society. For insofar as it belongs to the order of dream and vision, art isn’t part of culture. On the contrary, it is the intrusion of Nature into the human realm. And what the intrusion reveals, ultimately, is that in truth there never was “culture.” Words, concepts, beliefs, ideations are forces in a universe of forces. As Paul Klee said, if humans aren’t the masters of the universe, it’s because each of us is “a creature on a star among stars.” [5] To see things otherwise is to judge the world, to arrogate the right to decide on the purpose and nature of things that in reality exceed us.

Johannes Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance (1662) shows a bourgeois woman weighing gold and pearls strewn on a table before her. On the back wall is a picture of the Day of the Lord, when Christ will break into history a second time to judge all sinners. Vermeer’s painting has often been interpreted as an allegory on the sin of vanity, i.e. pride and egoism. If the woman is preoccupied with the value of the jewels, it can only be because jewels are scarce and exclusionary. As material possessions, they indicate her privileged place among mortals. Their value, itself an outcome of human judgment, augments her personal worth over other beings. The fact that she is facing a mirror lends support to this allegorical interpretation, as does the aforementioned picture on the wall. In Early Modern Europe, mirrors were still luxury items, and few things bespoke social status like an oil painting in the home. Vermeer’s inclusion of a picture within his painting speaks to what artworks in general signified in his time. Like gold, pearls, and mirrors, they were coveted tokens of prestige.

Given these signs, the viewer comes to an obvious question: Shouldn’t someone who takes the doctrine of Revelation seriously find better things to do with their time than count their riches? The juxtaposition of the figure’s activity with the image on the wall seems to imply a clear moral message. This woman would be better off valuing the “treasures of Heaven” over the “treasures of this world.” When we add that the painting has affinities with a tradition, widespread in the Netherlands of the time, of moralistic “vanitas pictures” in which mirrors and gold prefigured as symbols of vanity, the interpretation appears confirmed. [6] Vermeer’s painting contains a moral allegory, and not a particularly subtle one, what with the judgment of God looming in plain view. And like all allegories, this one asks us to judge. We are being asked to judge the woman in the foreground. “Look how vain she is,” the painting seems to be saying. “Don’t be like her.” You can imagine the pious nods of the upstanding bourgeois who clued in on this while gazing at the picture in some austere but proud parlor of Delft in the late 1600s.

But if the painting’s allegorical function finds its proof in the presence of that picture of Judgment Day on the wall, that same picture introduces a note of irony into the overall painting that is absent from most vanitas images of the period. In fact it constitutes an example of an aesthetic rift. Briefly, what I mean by a rift is a gap, breakage, inconsistency, fissure, excess, flourish or other imperfection in the otherwise smooth surface of a work of art. It is what sets certain works apart from the rest within a specific class or tradition. In Reclaiming Art, I argue that rifts are what make the difference between “masterworks”—perfect examples of form—and “classics,” which deserve that name precisely because they each belong in a singular class of their own. Looking at vanitas paintings of the seventeenth century, we find no shortage of masterworks. In fact, with its emphasis on the realistic rendering of material possessions, the genre was particularly well-suited to displays of technical virtuosity. Most vanitas pictures, however, are known today only to experts on the period and art history students.

Few would argue with the assertion that Woman Holding a Balance stands out of the lot. Likewise, few would deny that Vermeer’s work isn’t just a masterful example of a genre but a true classic, a singular work that stands on its own, defying comparison. On the other hand, many would probably resist the argument that this painting, which in the end portrays an everyday activity of the Dutch bourgeoisie, is an act of subversion undermining an entire moral order and touching on the non-human core of human existence. This is what I would like to demonstrate in the conclusion of this essay.

The Last Judgment

Vermeer’s picture, I believe, contains not just one but three rifts, each of which extends and transforms the irony of the overall picture in order ultimately to annul the judgment that appears, on the surface, to be its message. The first has already been touched on. It is the explicit reference to Judgment Day in a picture that clearly didn’t need it, given the fact that moral allegories were common, even expected, at the time it was made. The second rift has a self-referential or “meta” function. It is that this reference to divine judgment takes the form of a painting within a painting. Had the image been a bible on a lectern or an angel wagging its finger, the allegory would have remained intact, because the notion of an actual transcendent judge in whose name humans could judge the living and the dead would have remained plausible. But the fact that we are faced with a painting of judgement is significant. The woman is being reprimanded for her apparent love of luxury by an object which is itself a thing of luxury—and this irony appears to us within Vermeer’s own painting, that is, within another luxury item. No artwork can decry the “treasures of this world” without itself being such a treasure—not even a Cathedral or a Buddhist shrine. Absolute judgments can’t be communicated through art without relativizing themselves absolutely. An artwork may seem to communicate one thing, but insofar as it is art, it will express something else.

Aesthetic works are necessarily material in nature. Regardless of the message a work appears to convey, its existence inheres in space, time, matter, and energy. Materiality—stone in sculpture, light in cinema, movement in dance—is its indispensable condition. The beauty that genuine art brings into being is the beauty of matter itself. It is the sublimity of a Nature always transformed but never eliminated or replaced. No painting could deny this world of becoming without at the same time affirming it in beauty. Vermeer’s image points us to this truth. It shows us that beauty, meaning, and truth radiate from this world, not from the next. The very conception of a transcendent reality on the basis of which judgements become necessary and absolute as opposed to contingent and relative is, in itself, an idea in and of this world. It too is an earthly treasure. The painting transmutes judgment to discernment in a rift through which we see that all judgments are contingent. All of them belong to the sublunary world of becoming, because Being is a flux of becoming and nothing beside.

The third rift is the clincher. Whereas a true vanitas picture of the period—a masterwork—would have loaded the scales with jewelry, Vermeer leaves them empty. He thus ensures the failure of his work as an allegory even as he subverts allegory in every form.

As mentioned above, the allegorical interpretation demands that we judge the woman for her vanity. Seeing her weighing gold and pearls in front of a picture of Judgment Day, the morally upright viewer reacts with disdain and comes away with a moral lesson.

But since the scales are empty, the question arises: Who is doing the judging here? In reality, the only thing the woman has been weighing is the transience of the moment itself as an event in time. John Berger describes the effect beautifully in his 1972 documentary, Ways of Seeing:

Gradually, the painting becomes more mysterious, less easily explainable. The light falls on her face, on her fingers, on the scales, on the pearls. The moment has been preserved. And as we realize this … we also realize that like every moment, it was unrepeatable. It is as though she is holding the moment between her finger and thumb, in the scales of the past and the future. Despite its apparent celebration of property, this painting is about the mystery of light and time as we look up at the stars. [7]

Vermeer’s painting confronts us with the absolute immanence of a world without judgment. The fact that the scales are even is significant, as it tells us that only in immanence—immanence that is “not immanent to anything but itself,” as Deleuze puts it—is true justice achieved. This is why Nietzsche said that “only as an aesthetic phenomenon is existence and the world eternally justified.” [8]

So, it isn’t in the picture on the wall that we see the real Last Judgment but in Vermeer’s painting as a whole, which bodies forth the judgment against judgment that frees the cosmos from an anthropocentrism that would make the human perspective absolute. Though this universe includes humans, it also includes the light of the sun, the undulations of marine blue fabric, pearls produced over years in the shells of mollusks, gold forged over eons in the depths of the earth, and religious myths that are like the beautiful waking dreams of humanity. With judgment gone, all things are allowed to exist in an immanent frame. Revelation ceases to be a forever-postponed future event to become an ever-present unveiling wherein the world discloses its immediate suchness. “The apocalypse is the way the world looks when the ego has disappeared,” Northrop Frye wrote. [9]

The elements in Woman Holding a Balance form together a single miraculous event, a clash of forces, an explosion of the new—terrible, beautiful, and real. The painting enacts this event even as it embraces the judgment that would deny it. In the frozen moment where immanence irrupts into the imagination, there is nothing left to judge, not even judgment itself, because even the most anthropocentric act of judging is a non-human event shaping the human world. Is this what the voice in the Book of Revelation means when it says, “Behold, I make all things new”? Is divine judgment less a moral invective than a creative act through which the human world is restored to the innocence of the Real? That is what I think the myth on the wall is telling the woman. It is what Vermeer’s picture, I believe, is telling us. It is what art as a medium reveals all the time. Art liberates the forces that judgment seeks to contain and control. It connects us to a reality that exceeds human consciousness, even as it makes us the conscious creatures we are.

This essay is based on a presentation given at the Science and Nonduality conference in San Jose, CA, in October 2015. An earlier draft appeared on the Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice blog under the title “Consciousness in the Aesthetic Vision.”

Notes

- Anton Chekhov, quoted in Valentine T. Bill, Chekhov: The Silent Voice of Freedom, Philosophical Library, 1987, p. 79.

- Gilles Deleuze, Pure Immanence: Essays on A Life, translated by Anne Boyman, Urzone, 2001, p. 25.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, The Transcendence of the Ego: An Existential Theory of Consciousness, translated by Forrest Williams and Robert Kirkpatrick, Hill & Wang, 1960, pp. 48-49.

- Eugene Thacker, in a lecture: https://vimeo.com/groups/86415/videos/22862986

- Paul Klee, The Thinking Eye: The Notebooks of Paul Klee, edited by Jürg Spiller, G. Wittenborn, 1961, p. 63.

- Mark W. Roskill, What is Art History?, University of Massachussets, 1989, p. 148.

- John Berger, Ways of Seeing, BBC, 1972 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pDE4VX_9Kk

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 33.

- Northrop Frye, The Great Code: The Bible and Literature, Penguin Canada, 1982, p. 172.

![Vincent van Gogh, Still Life: Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers [DETAIL], 1888.](https://wp.cosmos.media/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2016/07/img3_VanGogh_detail1.jpg)