The Goddess as Active Listener (Parts 5–10)

Editor’s Note: The full text of this work comes in ten parts, which we have broken into three installments. For Installment 1: Parts 1–3, click here. For Installment 2: Part 4, here. Below we present the final installment.

5

When I remember Sue Castigliano, I think of almost naked dancers vaulting above the gold-tipped horns of Cretan bulls, to the sound of waves breaking in the distance. Wandering with the ghosts of an exploded island empire, I enter the doors of a library that I first thought was an octopus. When I think of her, I see wheat bound in sheaves, corn hanging from a makeshift wooden peristyle, grapes being stomped by rhythmic feet in vats. I think of the minute preparations of a glad community in the month before a human sacrifice.

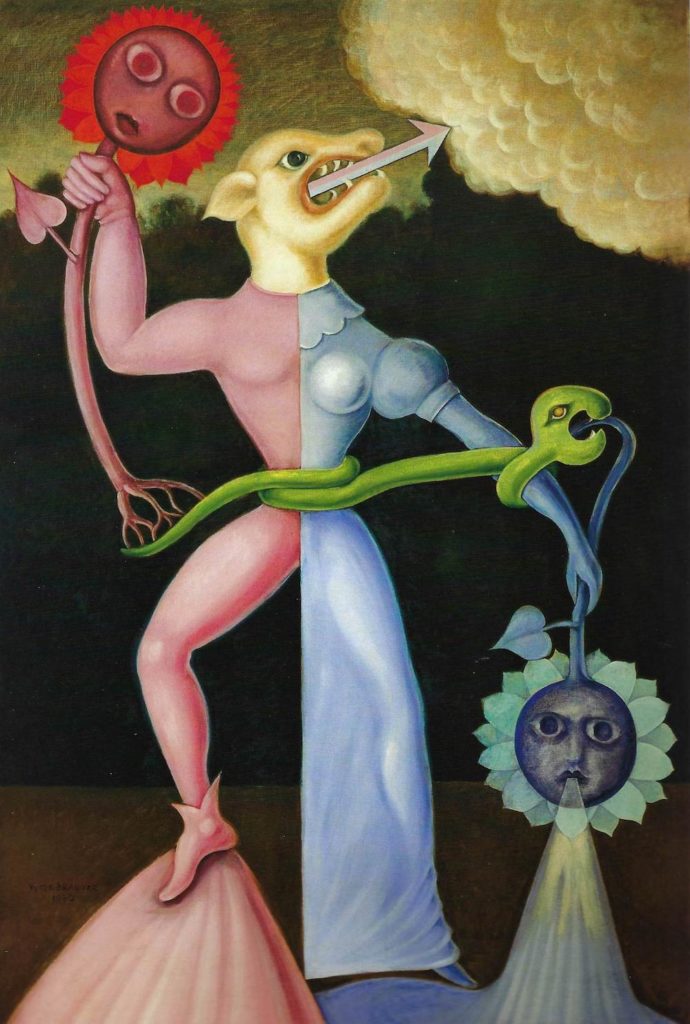

When I remember her, I think of a face that encompasses multitudes, whose each component is distinct, the dark face of the goddess, projected against lowering clouds. I think of Ceres, of Inanna, of Isis, of Coatlique, and of Oshun. I think of olive oil sleeping inside of prehistoric jars, the Sibyl smoothing out her wrinkles in the shadow of the arch of Constantine. I think of a young girl standing on a cliff above the sea, the wind playing with her hair, as she listens for the voice of her drowned lover.

Her body is the world tree. Her navel is Omphalos, the place of interconnection. Her womb is the cave where stars can get changed into their human suits. In her left palm Saturn, time’s comptroller, tilts and revolves. The fingers of her right hand touch the Earth with a gesture of abundance. And then, quite unexpectedly, she stands before me in a robe. In her eyes, I can see ships sailing back and forth. There, beneath the gigantic shadow of a wave, a wave that towers, still swelling, up and up, they go in search of a dock that is nonexistent.

Above our heads: a roof, whose beams have disappeared. There is only a charred corner. The shore is not far away. The astringent scent of salt is softened by the scent of moss and rosemary. “Beloved, come. Like fireflies, the ghosts of all past seers flicker in the dusk, where, if you hurry, you might catch one in a jar. Our fingers touching, like our souls, by its light we will read an elegy on the metastasis of Rome, on the triumph of the Age of Iron, the last statement by a master who is called by some “Anonymous.” Upon your lips, my breath: the elixir by which your name will be alchemically removed.

“Many years have passed since the day that you were buried, facing east, with a luminous stone clutched tightly in your hand, with much to say that would never be expressed. It is reasonable that your knees should start to tremble and give out. A drum beats in the distance, in the labyrinth of your ear. My pulse suspends you. Are you dead, or are you not, or is there some third alternative?

“In my eyes, you can see your culture, falling. Do not dare to look away! A slow spiral has returned you to this spot, and it will do so once again. You can even now feel how spaces open in your stomach, how your heart breaks with the ocean, how the sky reroutes the tangles of your nerves. And who is that small echo, now dancing on your tongue? As you fall into my eyes, you can even now feel how your thoughts are not your thoughts, how these thoughts belong to a figure that you lack the strength to recognize, how the wind sucks the marrow from your bones. There is more to fear than you know, but do not fear too much. We are free, in this silence, to calmly see and then celebrate the worst. Each throwing his/her arms around the other, as the light fades, we will weep.”

This is the role that my teacher acted out for me. It is not, of course, who she was in her day-to day existence. In hindsight, my memory manufactures images, which, no doubt, obscure far more than they illuminate, and yet they point to something not entirely untrue.

6

Oddly, there was nothing supernatural about her persona, quite the opposite in fact. She was a middle-aged woman from Ohio, about 42, the wife of an Episcopal priest, in no way unusual in appearance. She confessed that she found it difficult to lose weight from her hips and thighs. A few varicose veins were visible. The birth of two of her three children had been difficult, resulting in a number of physical problems. To me she was quite a beautiful, and even glamorous, figure. Her imperfections removed her—almost—from the realm of mythological fantasy. They made her real. Few noticed the live snakes that she wore instead of bracelets.

7

I am tempted to say that Sue Castigliano’s method was that of direct communication between one human being and another. To some extent this was true. One might note in passing the resemblance of her approach to the “logical consequences” theory of Dreiker, the “self-awareness” model of Meichenbaum, the “reality therapy” of Glasser, and the “teacher effectiveness training” of Gordon. In retrospect, I am surprised to see to what extent her actions were informed by developmental theory. When she interacted with her students, no abstractions were allowed to show.

A prerequisite for the guide is a mastery of what Buddhists call “skillful means.” The good teacher disrupts. He or she has a killer instinct for the best way to subvert the status quo. After interfering, the true catalyst allows nature to take its course. Speech class took the form of a circular discussion group, in which every voice could be heard. Sue would subtly steer but not dominate the conversation. She would set an idea in motion, she would set up a scenario, and then she would sit back to see what might develop.

One morning, for no apparent reason, I decided to attack a girl who had transferred from St. Peter’s High, the school from which I had been terminated, with extreme prejudice, two years before. I was outraged by her wholesomeness, and I finished a nonsensical diatribe by saying, “Did you leave your fuzzy pink bunny slippers at home? You should wear them to school. They would complement your outfit.” The girl launched herself across the room at me, swung once with her book bag, and then yanked with the intoxicated fury of a maenad at my hair. Its two-foot length allowed her to wrap it securely around her hands. When she had almost succeeded in removing it from my scalp, my psychopomp said, “Enough.”

Another teacher might have put a stop to things before they went that far. She later asked, “What do you think you said that made her so upset? Were you really angry with her, or were you angry about something else?”

8

I remember Sue’s response when I informed her that I felt I was growing stupider every day. I could not imagine what was wrong with me. My mind felt numb, and passively chaotic. My sentences self-destructed. My tongue was an alien artifact. It no longer fit in my mouth. Words flew across the horizon, to drift like litter through the streets of empty cities, to lose themselves on the other side of the globe. Could I really have become stupid? Was this a thing that humans did? An irrational fear, perhaps, yet there was no mistaking the symptoms. I could feel the active force of petrifaction, like a boa constrictor, coiling, each day a bit tighter, to squeeze the life-force from my neocortex. Pretty soon I would be too stupid to even bother to complain. My teacher did not argue, or offer to help, or in any way attempt to talk me out of the experience. Practicing a bit of reality therapy, she said:

“Why do you think that your stupidity is so unique? You do realize that there are stupid people all around you, and that one of them is speaking at this moment?

“I have been searching all week for an image for the end of the poem that I’m working on. It is right on the tip of my tongue, but it refuses to come out. You probably would not like the poem. It does not have any exclamation points.

“It’s about slowly getting up each day to change one small part of the world.

“I often feel as though I am moving under water. Everything seems too difficult. This morning I reached for a box of cereal on the top shelf of the pantry. My fingers were not long enough.

“I look at myself in the mirror. I am not young. The years just disappear. At times it does not seem possible that the girl that I used to be is gone. Who is this middle-aged woman looking back at me from the mirror?

“And then I think that I was able to reach the cereal box after all. The image that I am searching for will probably arrive tomorrow, or perhaps it will be waiting for me to notice it in a dream.

“My husband is a good man. I love being a teacher.”

It may seem odd that such a confession should have a liberating effect. The reason is not complicated. My teacher gave me permission to be human, to begin from where I was. It was wonderful to know that the goddess too had doubts. She also said, “Why don’t you keep a notebook to write down everything that comes to mind, stupid or not?”

Shortly thereafter I was inhabited by a swarm of primordial energies. Like an egg, the world cracked open. Tiny whirlwinds split the seed inside my heart. The “I” was shown to be an “Other,” just as Rimbaud had once theorized. At 2 AM one morning, to the sound of crickets chirping in a field, I wrote the first installment of my own ancestral myth—about 16 pages-worth in a matter of four hours. The writing was so illegible that it might as well have been cuneiform. It was a good thing that I copied it soon after. The piece had way too many adjectives, of course. How free and generous was my use of the exclamation point! I missed few chances to insert them. If memory serves, the piece was not especially good, or really any good at all, but that is not the point. It occurred to me suddenly and with violence, “You have the power to create.”

9

By contemporary standards, the “personal influence” model was no doubt pushed to an extreme, and then, in my own imagination, beyond that. This was the heyday of the counterculture. Boundaries were fluid. We would sometimes talk through the afternoon on the back porch of her house, sipping lemonade from tall plastic glasses and discussing the merits of peyote versus psilocybin, as the shadows projected from a distant war lengthened slowly across the grass.

Black pajamas from a Viet Minh girl would follow her burnt scent, flapping, turning this way and that in the cross-winds of the Pacific. With the banging of a door, the girl’s pain would slip into the wide heart of the goddess, there to find a home, there perhaps to find some tiny bit of rest. We could hear the blasts from the 30-foot mountain horns, along with the struck gongs, which together were like the sound of tectonic plates scraping. We could hear the interdimensional elephants trumpeting, with the blood of gods on their tusks. We could hear the Paleolithic bird-squeaks, growing louder, as the Nagas climbed from their atonal graves.

Troops would reenact on a cloud the opening games of the Mahabharata. Suddenly, we might note that the sun had vanished from the sky. Revolving on one spot, which just happened to be the spot where we were seated, the wheel of time would appear almost motionless as it flew. “Have you read Thich Nhat Hanh’s The Lotus in a Sea of Fire?” she once said. “In luminous prose, he explains the reasons that monks burn themselves. According to Hanh, it is not correct to call this suicide, as most Western reporters do. It is not really even protest. Can you imagine how much love it takes to set yourself on fire? He says, ‘In Buddhist belief, life is not confined to a period of 60 or 80 or 100 years: life is eternal. Life is not confined to the body: life is universal.’ By burning himself, the monk shows that he is willing to suffer any pain for others, not only to call attention to the suffering of the oppressed but also to touch and open the hearts of their oppressors. Hanh’s language is simple enough, but it has the force of great poetry.” A kind of natural hallucinogen was produced by the mere proximity of the beloved. A storm would make the oak leaves rustle. The scent of lilacs would overwhelm the senses. Rooting itself in the moment, the self moved deeper into incarnation.

10

Again, my teacher has moved into a dream that powers the perpetual beginning of the world, whose initiates will at length restore the transparency of space.

The beloved now becomes anonymous.

It is of no importance who or what she was, but only that she play each role that memory invents.

Falling as though from a distant planet, the shadow of Sue Castigiliano opens like a door. The footprints of a prehistoric goddess lead straight across a tiny but quite terrifying ocean.