On the World-Disclosing Rifts of Cinema: J. F. Martel and Christopher Yates in Dialogue

Editor’s Note: This dialogue came about through a correspondence between philosopher-filmmaker J. F. Martel and Christopher Yates of the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts, jumping off from Chris’ essay, “A Phenomenological Aesthetic of Cinematic ‘Worlds’.” The dialogue also refers to J. F.’s book, Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice. However, you do not have to have to be familiar with those texts to enjoy the present exchange of views. Rather, we hope this becomes its own branching-off point for further reading, conversation, and aesthetic experience—which might also lead you to (re-)visit the prior works, if you so desire. You are invited and welcome to share their your thoughts in the forum topic below.

Editor’s Note: This dialogue came about through a correspondence between philosopher-filmmaker J. F. Martel and Christopher Yates of the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts, jumping off from Chris’ essay, “A Phenomenological Aesthetic of Cinematic ‘Worlds’.” The dialogue also refers to J. F.’s book, Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice. However, you do not have to have to be familiar with those texts to enjoy the present exchange of views. Rather, we hope this becomes its own branching-off point for further reading, conversation, and aesthetic experience—which might also lead you to (re-)visit the prior works, if you so desire. You are invited and welcome to share their your thoughts in the forum topic below.

J. F. Martel

Your essay posits an aesthetics of cinema rooted in on Heidegger’s idea of “world disclosure.” As a work of art, a film presents a world that the viewer enters into by experiencing it. But through your argument, we get the sense that the worlds which films open up are more than mere fictions: they contain truth, and the truths they contain are truths of the world, of our shared horizon. Can you begin by telling me a little bit more about the concept of “world” as you understand it? What is a world? What is the difference between a fictional world and an actual world? And what part does the aesthetic play in world disclosure?

Christopher Yates

I think I first began to get absorbed into this issue of ‘world’ or ‘worldhood’ when I saw Wim Wenders’ 1991 film, Till the End of the World. On its surface the film is a kind of sci-fi suspense drama that crisscrosses the globe under the pending doom of nuclear proliferation, social-political strain, and all the unsteadiness of what would be 1999’s Y2K turmoil. Wenders plants a trio of characters thrown together through intersecting and agitated ties to money, science, theft, and then this fast-paced engagement with a kind of trans-humanist technological mechanism. Seemingly futuristic and hyperbolic, it struck me that the real story of the film is about who and how we are as people, as social and material creatures who live through unfolding ideas and commitments, and as beings catapulted through the web-like nets of the urban and rural, techy and earthy, trustworthy and deceptive. The film reveals these phenomena to us—these habits of living and thinking that were almost so obvious that we were failing to take notice, maybe even unable to grasp were it not for the intervention of art. Wenders showed us an example, I believe, of what you call “the weirdness of the Real” (15) behind the otherwise soothing trappings of our “hyper-aesthetic age, a time of phantom images and blinking lights, manufactured memories, and synthetic dreams” (134). To stay with your language, the film amounted to a revelatory ‘act of resistance’ that broke through the ‘cloud of artifice’, gave us a moment of ‘astonishment’, and maybe even re-instilled some ‘wonderment at being itself’ (126, 134, 16). These are the characteristics of what I am calling, after Heidegger, ‘world disclosure.’ Let me try to unpack what I mean.

I suppose I’ve already suggested something about how the ‘fictional’ character of film doesn’t mean it is reducible to a land of ‘make-believe.’ Films are storied, naturally, but so is life. So when we see a film like Wenders’ (or ones by Terrence Malick, whom I discuss in my article) we are bracketing one realm of narrative for a more distilled one. It’s not about moving from the ‘true’ to the ‘false’, or about exchanging ‘real life’ for ‘entertainment’—even if we sometimes approach movies that way. It’s about stepping outside of a default web of life experiences and beliefs in order to enter a distinct cinema-logical event of concentration that wants to reveal, or at least look for, the real story of what’s afoot beneath the normal staging of our lives. It’s not that films necessarily do this consciously in the terms I’m putting it, or that we necessarily ‘intend’ the revealing when we watch one. But it happens, at least sometimes. Artists train our attention, and this event can be a rattling and moving thing all at once. But still, so what? Isn’t a film more like a dreamy escape from reality? I think that what we call day-to-day ‘real life’ is itself already an abstraction—not a falsehood per se, but a situation in which we are living ‘through’ and ‘according to’ a whole host of plots, structures, patterns, and ideologies that we absorb and sometimes determine as our existential logic. It can be hard to admit this. But just consider how you feel when you are stuck in traffic or placed at the mercy of some technological glitch: Why am I compelled to live on these terms?

Still from Wim Wenders’ Till the End of the World

Once we relax our assumptions about the rigid divisions between true and false, fact and fiction, lived-logic and cinema-logic, then we start to get into the issue of Worldhood. Heidegger describes our lives as a phenomenon of being-in-the-world. No kidding, right? But his point registers a couple key shifts in common ideas about the self. First, he’s saying none of us are fixed, fully defined, or utterly individual entities. We don’t exist in the manner of a fact, or have a classified nature or identity like some element on the Periodic Table we all met in high school chemistry. Second, his hyphens point out the existentially contextualized nature of the self—the how of the self rather than the what of the self. We ‘are’ beings, yes, but the way we have and hold our being is more like a canoe navigating a river than an anchor planting us in place. He’s not relativizing our selfhood into some trippy carnival of unmoored existence (I’m mixing metaphors), and neither is he saying we are utterly determined by our contexts and constructs. He’s saying that the kind of being that a human being has is an unfolding and relational event. What is relational about it? First we relate to life in a distinct and underlying mode: we live out questions of ‘meaning’, even subconsciously. We carry out our ‘being’ as insatiable seekers and questioners. Second, we are always already relating to what I’ve called the web of relationships, patterns, and ideas that are simmering (and themselves searching) around us. The first quality is what animates our being-in; the second quality is what animates the-world.

Words like ‘culture’ and ‘society’ get close to this notion of Worldhood when they refer to the web-like nature surrounding our project-oriented lives. But we shouldn’t think in objectifying or categorizing terms here. Worldhood can include everything from architecture and urban ecology to social/political/religious institutions; from the signifying function of small gestures to the communicative function of social media; from chalkboards to PowerPoint; from barista-tipping to international trade agreements. If the self is like an actor in a theater, then the World includes everything from the stage to the lights, acoustics, makeup, wardrobe, seating, director, audience tastes, theater districts, critical reviews, Tony Awards, and so on. To be clear, world is not just an aggregation of social stuff. If you and I are unfolding, meaning-seeking beings, then world is at once the terms on which this happens and also the pulsing products of these very terms and their histories. It’s an ongoing spiral. Heidegger would say that we can never get a totally objective view on Worldhood—we’re inside it after all. Just as we are tossed into Language and thus enabled to speak and think and write on its terms (for better or worse), so too we are tossed into World and enabled to live out our ‘being’ (for better or worse) on its dynamic terms.

Let me give a personal example. A few years ago I traveled to Montreal for the first time from my (then) home in Washington, DC. As soon as I got moving into the city I felt hit with a welcome wave of all these touchstones and reference-points that the locals were living by—everything from the bicycles to the buildings and parks, the sounds of French, the smells of cafes and used bookstores. (I went in summer, but not with a tourist agenda). Don’t hear this as romanticizing. I just walked and walked and marveled at the way this Montreal ‘world’ was happening—was coursing around me. I was on my own and away from my normal world-navigation, and I felt this. At the same time I wasn’t ‘in’ the Montreal world either, and I felt that too. I was still me, but I didn’t have any real rooted traction for carrying out my own self. I didn’t grasp the Montreal or DC worlds ‘as a whole’, but felt sort of ‘middled’ between them. I wasn’t in a position to literally ‘make’ sense on the terms of either place. It was a little lonesome, but also something to savor—because it recalled me to a place in which one undergoes life as possibility rather than pattern. I think the experience is a bit like what you describe as being ‘caught unawares’ by ‘the strange and uncanny in life’ (16-17). For me it was a felt and thought recognition of this matter of ‘world-disclosure.’

Of course, we don’t have to travel in order to grasp these phenomena. Let me come back to Heidegger and the larger issue concerning how the World we are ‘in’ has a storied character of its own—one with many plots and wagers of catharsis. This is neither good nor bad in its own right. But it can, according to Heidegger, become a real problem. It becomes a problem when we just live in a default way according to these terms—specifically, when we let our own meaning-seeking side of being-in unfold according to certain grammars of the-world that are actually diverting, coercing, overconfident in themselves, deceptive, seductively persuasive, etc. It is easy, but not wrong, to cite our consumer- and technology-saturated society as a case in point. It’s not that these vertebrae of our lives, so to speak, are utterly bad, but that our default aspirational involvement in them is usually so unreflective that our existential posture gets all out of whack. These are cases of what Heidegger calls ‘Theyness’ (Das Man) that tend to derail us into inauthentic modes of ‘being.’ Nietzsche called it the ‘Herd’ mentality. Kierkegaard called it ‘idle talk’, among other things. In short: we conduct our lives and beliefs on terms that are set for us by a social momentum that promises us—literally—the world, but can actually conceal us from ourselves. The situation is similar to what Plato said about how we live in the cave amid ‘shadows’ of bad ideas and need the ‘light’ of wisdom. But the situation today is actually worse: we live in the cave and we venerate the shadows, convincing ourselves they are either the light itself or something even better.

Still from from Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life

One irony in all this is that our filmmaking and film-going situations—broadly put—are also shot-through with a Theyness manner of Worldhood. We all admit this when we joke and fuss about ‘Hollywood.’ Maybe some people feel that even a Wenders or a Malick is not immune to this. But what fascinates me is how they reveal to us the ‘world’ of our being-in, gift us a rare chance to concentrate on it and think about it, and spur us toward a lived search for meaning that treads cautiously with Theyness.

Here I’d like to turn back to your own work, JF, and ask you to elaborate on a couple points that I suspect are like-minded with these Worldhood issues—but maybe have a finer edge to them. First, in your ‘Postmortem’ chapter you extend your work on the way art signifies meaning afresh, recalls us to radical mystery, interrupts familiarity via strangeness, and even (in the case of Moby Dick) deploys a kind of madness against the reign of artifice. Here one specific application you flag is this: “Art implies the total dissolution of the person as a discrete unit that could be removed intact from its environment” (133). Would you say that this unique power of art fits with the features of what I call world-disclosure and the way human ‘being’ operates in this being-in kind of way? If so, I’d like to hear you elaborate on the scope and quality of this ‘madness’ you find art capable of manifesting. I spoke of film’s unique mode of ‘concentration’—would you say that this feels like a form of ‘madness’ at times, and is there a way in which we as viewers are somehow supposed to let it happen ‘to’ us? My second question is related. I’m interested in this notion of the ‘Rift’ that you take up in the middle of the book. You say it is a kind of break or interruption that takes place within a work of art, one that messes with our default modes of meaning—it “breaks the consensus trance and opens the work onto the chaosmos of the Real” (84). I suppose I’ve touched on this in terms of the exchange between a viewer and a film (or me and Montreal), but you are going much further into a phenomenon that happens ‘within’ a work of art itself. How do we know we are experiencing a Rift, and is the artist knowingly curating the situation to trigger this effect? Is the Rift a specific instantiation of the Madness effect mentioned above?

J. F. Martel

J. F. Martel

Your description of world-disclosure resonates with what I’m trying to say in Reclaiming Art. I love what you say about films opening up a space for reflection—that is, a space where we can make out our own “thrownness,” our own being-in-the-world. This is something that comes across very strongly in your essay.

If I understand you correctly, to live unreflectively is to engage blindly with the world around us as though it were the only possible world, as though it were the real itself. There is something in cinema that confronts us with our own relationality, conveying to us how everything that makes us what we are involves a relation with an outside, a world. Thinking about cinema, I often get the sense that the term “world” becomes more meaningful if understood as a mass noun like “milk” or “water” and opposed to the vague materialist notion of “matter.” What cinema conveys to us is that we are not primarily made of matter; we are made of world. World is the substance of our reality. Beyond this, there is little I could add to your brilliant analysis of this concept.

Another part of your response that really speaks to me is your breakdown of Heidegger’s concept of being-in-the-world into two facets. First, there is a being that experiences itself as distinct (the fact of its experiencing itself that way should be all the proof we need that it is there). Then, there is the fact that the manner of this distinction, of this uniqueness, is completely relational. You use the example of a canoe on a river and it certainly works. But if we stretch the metaphor even more, we could radicalize Heidegger’s claim. Because it seems to me that every aspect of a canoe—its shape, its raison d’etre, its materials, all of the four causes—is determined by the environment of the river. The canoe has the shape it has by virtue of what the river (and the canoers of course) require of it. Similarly, the river is also a relational being, its shape and course being determined by its environment, by geological history, etc. The distinctive part of the canoe—its innermost being—does not inhere in fixed properties but in the mode of this or that particular canoe. It is not an element or particle so much as a way, a movement or course. So in a deeper sense—and let me know if you disagree—the bipartite nature of being-in-the-world is a provisional notion. Even the distinctive, pure being of a person is itself determined through a set of relational elements, points of contact, points of relation with the world. The singularity of a being inheres in its manner of unfolding and deploying itself. The soul is a style, so to speak. At least, that’s the basis behind my claim in Reclaiming Art that if you were to extract the character from its setting, there would be nothing left, not even the distinctive part, the is part.

To answer your first question, it seems to me that no word better describes the experience of realizing one’s constitutive relationality than “madness.” There are other terms I could have chosen to describe the “art effect,” of course, “ecstasy” being the most obvious one perhaps. But that term has associations with bliss and pleasure that I don’t think necessarily apply to every case of aesthetic engagement. Madness is a more expansive term, but suitably dramatic for describing an experience that upends the common reality we are normally convinced is the be-all and end-all of the possible. To go mad like Ahab is to wake up to the dream of life, to see that everything we are made of is always-already caught up in forces that exceed us, forces that we can’t even qualify as human (the white whale). The madness that great films and other artworks bring about inheres in the realization that we are puppets, but puppets that are alive and can acquire true freedom in that flash where our inexorable being-in-the-world becomes clear. Maybe this form of madness marks the spot where the reality in the illusion is revealed, and fate gives way to destiny.

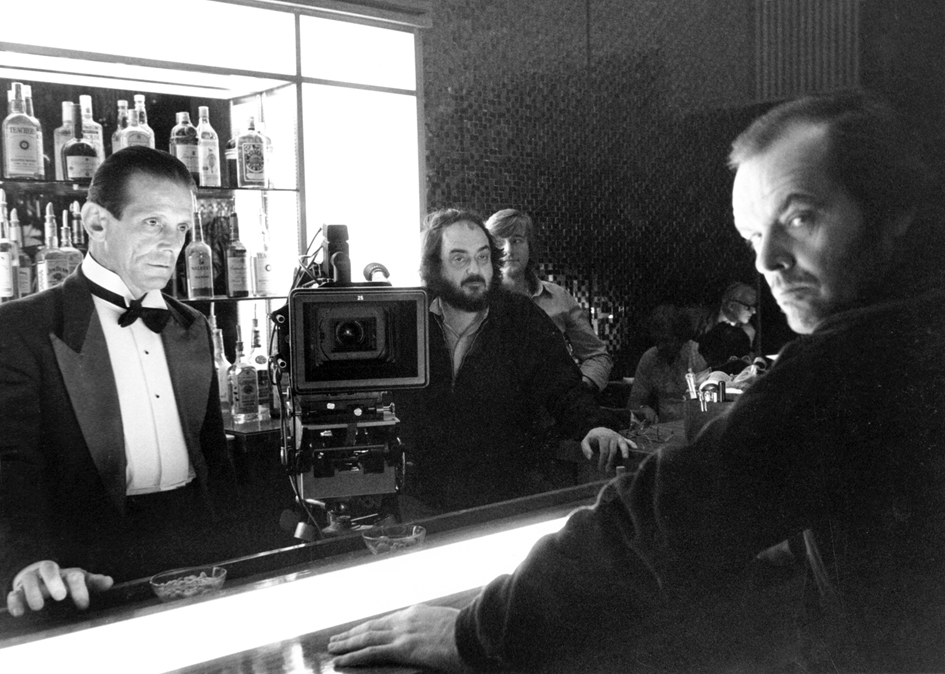

On the set of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining

The idea of the rift comes out of all this. That moment of madness when you suddenly wake up to the dream occurs as a sudden event, a tear in the fabric of the common world that is in truth only a partial apprehension of the real. It’s this event that I call the rift. Your description of that day in Montreal is a beautiful example. There is a sudden interruption of the sensorimotor sequence of cause and effect, and one suddenly finds oneself seeing it all from an oblique perspective, like the viewpoint of the unnumbered Fool in the tarot.

When I say that rifts also exist in the work of art itself, what I mean is that a great work of art will not totally conform to a given audience’s expectation of how the world ought to function. In order for the work to hold up, the visionary artist will inevitably have to break some of the laws of his time (laws of scale and perspective, of psychology and behavior, of physics, etc.). One must transgress the assumed finality of the unreflective world, one has to cheat “reality” in the name of something more, well, real—the Real, or the truth, or whatever. Think of the sculptor who, in order to express her vision, must give her statue a pose that would be impossible for a model to pull off. This instance of cheating leaves a rift in the work, a crack in its shell that gives the percipient an entrypoint into the deeper forces that go into shaping moments of experience.

The continuity error in cinema is probably one of the most potent examples of this. Sometimes, a continuity error violates a purely mechanistic naturalism in the name of connecting to a more expansive reality. There are many examples of such “errors” in the history of cinema, but the one that comes to mind is the layout of the Overlook Hotel in Kubrick’s adaptation of The Shining. The hallways and doors don’t match up. If you were to draw a floor plan of the Overlook based on what is shown in the film, it wouldn’t make sense—it would be a topsy-turvy place like something from Alice in Wonderland. But this hardly lessens the film; on the contrary, it draw us deeper into a labyrinthine quality echoed in other aspects of it: characterization, dialogue, plot, etc. It gives the film the non-Euclidean architecture its themes call for, turning it into a space where the borderline separating what we normally call the mind from what we normally call the physical world becomes porous, if it even exists at all. It doesn’t matter whether Kubrick intended these “errors” or whether they just occurred as a byproduct of the production process. Either way, the errors broaden and deepen the power of the symbol that is the Overlook Hotel. Realism is jettisoned in the name of reality.

Great works of art contain rifts of this and other kinds because they are putting us in touch with an objective reality that transcends any particular historical episteme—and that’s what I would argue makes them great. It isn’t so much that a good movie will bring you to an other world that lies beyond this one, but rather that it simply reminds you of the “worldness of the world”—of what Heidegger called facticity. Like all art, cinema confronts us with the eternal nexus of forces that makes up all particular historical worlds. It’s in this sense that, in my book, I claim that art is objective. The aesthetic conveys to us the eternal truth of facticity.

Maybe that’s going too far, or maybe it’s not going far enough. I’d be very interested to know if there is any divergence here between our ways of thinking on these points. In particular, I would love to know what insights your studies and reflections have given you into the nature of the symbol, a concept that undergirds much of what I just wrote. It’s a concept that I continue to struggle with, even as it keeps yielding new paths and territories. What are your thoughts on the aesthetic symbol and its importance in imagining the nature of art and cinema?

Christopher Yates

Christopher Yates

These are great thoughts and I’ll respond by peeling back a few more layers of the following themes: the world of artistic knowing, the astonished imagination, and the character of symbol. The issues definitely overlap and maybe we can say that your idea of the Rift is a linking thread.

First, what you’ve added to this idea of World brings in a depth of ‘setting’ and the kind of meaning that happens around us in the web of relationships that shape and carry our own path through life, and where past, present, and future are all animated in each moment. If that’s the case then Art is a kind of provocation back to the fullness of experiencing this—almost like a thing we ‘do’ in order to expose us afresh to a ‘doing’ that is greater than our so-called ‘autonomy’, an event that retrieves these pulsations of a ‘real’ that is more intrinsic to life than the machinations we are so often inclined to take as real. I don’t mean that Art reveals to us something ‘transcendent’ in the sense of being above or beyond the ‘immanent’ (though that may be), but something that transcends our default modes of relating to life and things through so many superficial mediating structures. I also mean ‘transcendental’ in the sense of going down into the underlying structures that creatively constitute and keep launching the better possibilities of our relational ‘becoming.’ You speak in Reclaiming Art of art as “innately emancipatory, being itself the affirmation or sign of freedom” and of how it involves us in “a sense of radical mystery” (130). I’m with you. The work of art “is perpetually new” and engages our Imagination “at the limits of reason and judgment” (130). The point is not that art authors our progress toward the ‘next’ new ‘thing’, but that it reawakens our sense of the infinite in the finite, an infinite that is always flowing—sort of spiriting us back into the deeper artistry that carries us.

Let me try to add to this by linking two figures in a bit of an anachronistic way. First, there is Mark Twain and very interesting point he provokes in his “Old Times on the Mississippi” from 1875. He talks about learning to pilot a vessel on the river as a young man, and the overwhelming task of having to learn “the shape of the river according to all these five hundred thousand different ways . . . If I tried to carry all that cargo in my head it would make me stoop-shouldered.” He’s showing us how that way of putting it assumes one mode of ‘knowing’ how to perform a relation to the river. He calls it a kind of ‘science’, to be sure, but one that ends up requiring a science of a different sort. You learn the shape of the river, he says, “and you learn it with such absolute certainty that you can always steer by the shape that’s in your head, and never mind the one that’s before your eyes.” Notice how he humbles logical certainty and turns us toward a more tacit knowledge, a felt relationship to the river, one that ‘knows’ it by being involved in it. He continues: “The face of the water, in time, became a wonderful book—a book that was a dead language to the uneducated passenger, but which told its mind to me without reserve, delivering its most cherished secrets as clearly as if it uttered them with one voice. And it was not a book to be read once and thrown aside, for it had a new story to tell every day.” We can call this an experience of World, or ‘worldhood’ as Heidegger might say.

Chop wood & carry water, Herr Professor—Ed.

Another angle on this issue comes from the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy in some essays of his from the 1990s. He speaks of a ‘sense of the World’, a kind of meaning that belongs to the topography of life in a dynamic, ever unfinished way, a way that doesn’t rely on human knowledge to be accredited as ‘true.’ So, to speak of a sense of the world would jettison the idea that we ‘make’ sense of it, that we crack its code or bring meaning to something inert. His metaphor is the desert as opposed to the laboratory. He says a funny thing: “Existence tans its own hide.” He means that the deeper ‘being’ of reality has its own agency—it wears a skin and writes a story that we wrap around ourselves, or at least we should. Nancy is trying to get away from what philosophers call a Subjectivist or Anthropocentric take on how what you would call the ‘real’ happens. In other words: we aren’t the center of everything in terms of how ‘sense’ (meaning) is ‘made.’ Nancy’s notion of ‘world’ is a little different from Heidegger’s. He doesn’t quite mean the webs of cultural relationships through which we have our being-in, but more the realm of what Heidegger would call ‘earth’. When Nancy speaks of the ‘desert’—an expanse of world in which ‘sense’ is always simmering, always coming, the question is how to recover this place of understanding, and that’s what I think Twain was performing in his own way. (I see I’m now mixing metaphors of ‘river’ and ‘desert’). Nancy, importantly, thinks that Art most of all can help us in this. But Nancy goes a little further than Twain and, indeed, Heidegger. He says we really have to push our focus on Self (Subjectivity) further to the side, otherwise we keep insinuating our own privileged position into this whole business of existential meaning. I get that, but I think he goes too far (and I suspect you would agree with me). The sense of the World and the ‘sensing’ nature of the Self are really a collaboration. Even Nancy’s ability to make his own contra-Subjectivity point assumes his own agency, and so winds up in a bit of a contradiction.

Ironically, at times the philosophical tendency to wrench us from the primacy of Selfhood ends up becoming a fetish of that very self. Do we see this tension played out in contemporary art? One wants to evoke something greater than the artist or the given work, but then we lapse into the gravitational pull of commodification and art-stardom. So then the question becomes, with Twain: How do we pilot the river without reducing it to an object or inflating ourselves into heroes and heroines? How do we move the cargo of life yet stay attuned to a movement that’s carrying us? Getting back to our Canoe, I would here agree with your point that “the bipartite nature of being-in-the world is a provisional notion. Even the distinctive, pure being of a person it itself determined through a set of relational elements, points of contact, points of relation with the world.” To me that keeps the fact of what I’ve called Subjectivity (what Heidegger called Dasein) but reminds us of the coefficient, so to speak, that’s behind it. The Heideggerian account of how we live out our ‘sense’ in the world goes with Twain and Nancy’s reminders that this must involve us in a ‘sense’ that is bigger than us.

Would you agree with my agreement? I would only quibble with your use of the term ‘determined’ since that has a touch of a fatalistic vibe—one that seems to foreclose on the kind of ‘emancipation’ you have in mind for people as they return to contact with the ‘real’ of meaning. I think you mean something more like ‘constituted’ or ‘enabled’? Either way, I suspect we are both getting at how the way in which humans have their being in the world, or try to ‘make sense’ of this phenomenon, isn’t reducible to a choice between the ‘sensible’ and ‘intelligible.’ It isn’t reducible to a choice between modes of ‘feeling’ and modes of formal ‘logic.’ The way we are being-in and being-toward the ‘real’ is a mix of what the Greeks called mythos and logos, and so the way we try to understand all this needs to follow suit. I think we can call this the ‘logic of the imagination,’ and I think that is what art, broadly understood, enacts.

This brings me to my second theme: the astonished imagination. In Reclaiming Art you speak of the Imagination and Imaginal as a counterweight to the problem of Artifice. For example: “In the creative imagination, things are revealed to humans that are hidden from the rest of the known cosmos” (12). Art is “the prime fruit of the imagination” (12), and in this dimension of ourselves our consciousness has “access to a powerful otherworld, the place of dreams and myth, poetry and lunacy” (13). And later: “The Imaginal can lead to truths that don’t jibe with conventional expectations, sound reason, and common sense” and “if the symbols that come our way have a secret purpose, it is to reveal to us what we most need to see—and so are most afraid to see—in the moment of encounter” (77-78). The problem is that artifice and illusion (26-27) stand in the way—specifically of our rich (though vulnerable) ability to be ‘affected’. Am I getting this right? Affectivity is railroaded by media saturation, informationist views of what counts for knowledge, and advertising as the primary arbiter of our relation to images. These are instances of what you call the ‘kinetic’ forces that prey upon that kind of ‘affectivity’ in us that otherwise readies us for experiences of the ‘Imaginal.’ Affectivity is fed ‘artifice’ and in turn wants more of it, and more and more. “Proper art,” by contrast, “stills us”—it recovers a better path for our affectivity (27). Maybe we could put it this way: affectivity intuitively wants a shot at the Imaginal, but artifice steps in to curate the show and feed us a steady supply of doxa (common opinion) that we, ironically, cling to and upgrade and download as little badges of our own perceptual savvy.

I think these issues clue us in to what’s inspiring your work on astonishment (14), bafflement (21), and all that we feel as strange/weird when art, in its singular way (49-50), shakes our shoulders with the real. And when the Imaginal really is animated for us we arrive at a place where we can speak of truth in a distinct way—“the truth of absolute mystery” (61). That point goes back to one of your earlier points: “art is an objective pursuit with the same claim to truth as science, albeit truth of a different order… [and] art is a distinct sphere of activity with its own ontology. My belief is that what the modern West calls art is the direct outcome of a basic human drive, an inborn expressivity that is inextricably bound with the creative imagination” (20). And “[A]rt bears witness to the bafflement that the mere fact of existence elicits in our brains, which the imagination has cleaved from the rest of creation” (21).

These are great points. I’m trying to imagine how they would go down if you were giving a talk at the Guggenheim or MOMA, or some gallery opening in Chelsea. So far mostly good, I think, except there might be some head-scratching on this ‘truth’ business, which you link up with radical beauty and even morality. I want to point out that you actually enact a dose of the ‘astonishing and ‘strange’ in your own writing when you talk about these phenomena. You write: “Radical beauty is the resplendence of novelty in the deepest sense of the term, the sudden emergence of the strange that lay concealed in the familiar until now” (52). And you think this experience can dispossess us of the charades of artifice and return our affectivity to the course of astonishment as it relates to the imaginal. As an example, you even say that the Modernist movement wanted to go beyond beauty in order to come back to real-life experience (43-44), but then found Beauty in another form—a more ‘expansive’ beauty that “embraces the chaotic, the asymmetrical, and the disordered” (44). It’s almost like you are saying such beauty in art (with its attendant truth and morality to some extent) persists and waits for us on the other side of (1) artifice, and even (2) artistic drives that have drifted into thinking beauty is itself an artifice.

Either way, I think it’s safe to say that at this point you would lose your self-consciously avant-garde Manhattan audience. And I sense you know this. Am I right? Maybe you would lose their ideological bent but still speak to an abiding spiritual bent. I understand that critics and theorists today might be reluctant to speak of beauty because of its traditional affiliation with truth and goodness as the norms great art was meant to convey and inspire in its publics, or with Kant’s formalist stress on it as the very mark of great art. But I sense that in your book’s broader philosophy of ‘expression’ you are ‘reclaiming’ these principles, albeit in a different light than metaphysical and ecclesial traditions of ‘aura’ might think them. Perhaps this point about how radical beauty happens to/through Modernist art could itself be considered an art-institutional example something like the ‘continuity error’ you speak of in regards to film, where a ‘mistake’ happens that allows the ‘real’ to upset the domain of so-called realism?

Still from Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas

Even if that is an awkward extension of your point, there remains something in the focus on imagination that allows us to continue speaking of a certain Madness that adjoins this perseverance of beauty, truth, and morality. I’m thinking of how Plato (!) embraced a certain madness crucial to the operations of imagination in reason. A lot of people stop after Book X of The Republic, where he disses poets and paintings and seems to set an austere Apollonian course for human reason and social formation (I disagree with this interpretation). But in The Phaedrus he takes Socrates out of Athens and puts him in the countryside along the banks of the river Ilissos. This ‘rift’-like setting images the unusual nature of the dialogue between Socrates and the young Phaedrus; they are dealing with issues on the margins of everyday discourse but at the heart of Athenian worldhood. The central issue is the rather charged theme of eros, or loving (usually lustful) desire, which Socrates believes to be important but fraught with many perils—among them selfishness, power, manipulation, excess. Eros is a form of madness, and yet this doesn’t mean that love or madness are bad in themselves. Human desire can cloud human reason, yes, but there is also a loving, longing madness in reason itself. The trick is to learn how to hold together the desires of love and reason in a maddeningly wise way. Eros and Logos are intertwined in our desire to understand the truth of the cosmos—the order of things—and we seem wired to attain this understanding through some kind of ecstatic vision, literally a sight of higher eidetic (imaged, figured) truth. Sometimes without even knowing it, we desire truth in the mode of True Beauty, and the discovery of this is like the fulfillment of a search we have been living out across all manner of our desires. The madness driving reason and love is like half a symbol groping about for its other half that completes it. I hear all of this in your theme of the astonished imagination, but you might not be conceiving it in this way.

Still, I think that this is a side of Plato that can corroborate your points. And here we can turn to a third theme, one you asked me about: the symbolic. In Reclaiming Art you say: “Symbols are not a form of code for communicating distinct concepts. They do not represent—they are precisely what refuses to represent . . . . The task of art is to capture the symbol and preserve it in a sharable form” (68). The point relates to your distinction between ‘expression’ and ‘communication’, where communication is about just “reducing things to signs” but expression (more deeply) consists in an opening onto an “imaginal dimension” in a singular way by means of how the symbol animates an aesthetic event (69). The idea, if I understand you, is that what symbol does is related to what astonishment involves and to how art can relate us to the strange that is at the heart of the real. You say that a symbol “calls to us” and indeed ‘confronts’ us with “the unfathomable” in a way that exceeds the normal semiotics of referential sign systems. None of this is tidy and formulaic. The symbol “always comes as a problem or enigma . . . . symbols are constructs of the primeval chaos that precedes and envelops the coherent order of things” (72-73). Your discussion would have fit well in the Phaedrus, perhaps pushing Socrates still further into the aesthetic promise of madness, and perhaps even speaking from the position of the poets (to whom he left the door of a defense open at the end of the Republic).

What you open up here, and I think rightly so, is not that the function of symbol in art-making and art-experiencing is to deconstruct the idea that there is some order of things, but rather to draw us into the ongoing experience of a kind of madness at the heart of that order. This idea that Symbol exceeds normal conceptual reasoning—but doesn’t per se oppose such reasoning—is very important. Symbol, as an experiential phenomenon, operates like what I have called (following Heidegger) ‘world disclosure.’ Artistic ‘expression’ discloses something via the symbolic, but also holds something back such that mystery is preserved and we are enabled/invited to again ground our existence in some kind of enlivening question rather than logical answers.

I hear you saying something similar to what Hans-Georg Gadamer has said in his book, The Relevance of the Beautiful. I like his ideas very much because instead of ‘explaining away’ the expressive wonders of art he draws us ‘inside’ of them. He reminds us that the notion of ‘symbol’ goes back to the ancient Greek practice of hospitality, where a host broke some kind of special token in two and gave one half to his guest as a pledge of kinship, a tessera hospitalis. The idea is very much like how Plato said that the logos of eros has to do with how some part of us has been broken off from the beauty of truth and longs to rejoin it in an experience of wise madness. Gadamer says the phenomenon of the symbol is one of being a fragment that wants to relate back to a whole in an experience of love—an experience specified as “the beautiful in art” (32). Symbol isn’t about signifying some whole that is known or encircled in advance to then become our possession. He’s really talking about the symbolic character of artworks as works themselves, and not so much about the presence of symbols within a work (such as ‘Rosebud’), although I suppose the point holds on both fronts.

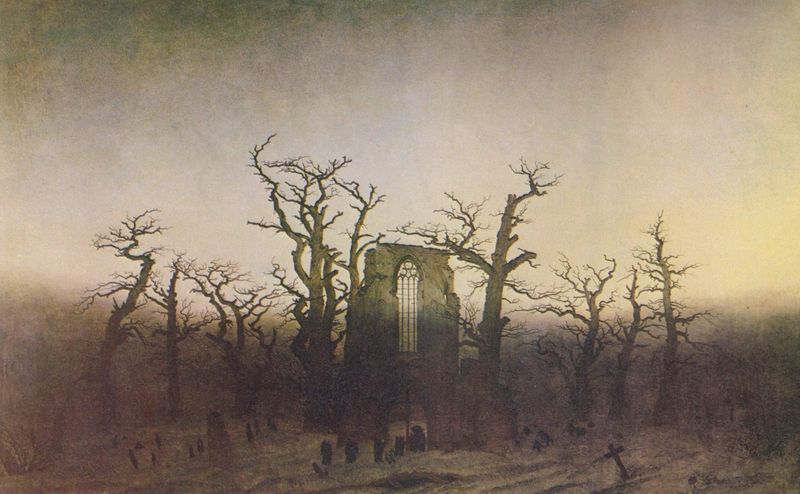

Caspar David Friedrich: Abtei im Eichwald, 1810

Again, and like your point I think, the symbolic is not about getting us into the comfortable refuge of a governing ‘concept.’ What Gadamer calls “the particular sensuous language of art” is not an equation solved by coordinating two sides of the equal sign. Contemporary art especially, he says, shows us how the symbolic “rests upon an intricate interplay of showing and concealing” (33). It shows us the path of an attunement to the real as it resides within a relationship, like that between host and guest. We might say that artworks are like the literal threshold residing at the heart of hospitality. And what the symbolic at the same time ‘conceals’ is some “total recovery of meaning” as though such a thing could be represented at all. Our experience of truth is, after all, always finite, and the experience of the symbolic roots us in the abiding wonder that really is there, moving on with madness and hope. Here the language of ‘representation’ turns out to be unhelpful because it can still imply that art is waiting on some kind of conceptual accreditation—some kind of big truth that is re-presented or re-ferenced by some little artistic gesture. In a way, the symbolic ‘is’ the real, or maybe we could say the ‘way’ or the ‘how’ of the real. The sensuous representation of our relationship to some promise of an unfolding order ‘is’ present. The ‘fragment’ is itself the point and not a means to the point (that would be allegory, as traditionally conceived). Gadamer says: “The significance of the symbol and the symbolic lay in this paradoxical kind of reference that embodies and even vouchsafes its meaning . . . Thus the essence of the symbolic lies precisely in the fact that it is not related to an ultimate meaning that could be recuperated in intellectual terms. The symbol preserves its meaning within itself”(37). (Perhaps, if you’re agreeing with all this, you could well have titled your book Vouchsafing Art). We don’t just stand there and let symbolic expression wash us into itself. We have to act—constructive engagement with the interplay of revealing-concealing is demanded of us, and this is a special thing. We might even say that the symbolic character of art operates kind of like a practice of ‘faith’—where faith ‘is’ the point as opposed to being the plaintive hope for ‘a’ point.

I see this very thing at work in Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings. His use of staffage set before the backdrop of incredible natural landscapes in the heavy and wondrous hues of dusk shows three things: (1) human existence is a journey grounded in some kind of direction-pulled contemplation, and (2) we aren’t the center of this existence in some authoritative way, and (3) the center or what we’ve been calling the order of things consists in an ever-unfolding play between our journey and a hovering expression of a reticent but resilient beauty of truth for which we intuitively long and sometimes feel in a radix kind of way. Let me give a more mundane example. Think of those instances when you sometimes ask someone for directions to get some place. Sure, it’s a ‘conceptual’ affair—you want the utilitarian logic that gets you on the assured way. But something else is afoot. To look someone in the eye and receive their directions is to undergo their care and to practice a trust in their trust in a right pathway. They are pointing you forward as in a semiotic reference, but they are also ‘hosting’ you in the relationship they have to the very possibility of being ‘on’ the ‘way.’ It is a threshold moment, and some part of us genuinely savors this, right? Once, when I was visiting Spain for a very brief trip, I was besieged by anxiety (here we have an amendment to my Montreal example). I was immersed in the symbolic glories of Granada’s art and architecture but I had no sense of living in relationship to their pledge of order. What I ended up doing—frankly in a spirit of desperation—was asking locals for directions to places I already knew how to get to. I just wanted to live in that little yet awesome care of a guest-host threshold. I think the same thing drives us to experience art, and drives some artists to make art.

If I could put a recent art example on the table here it would be Pavel Lungin’s 2006 film, The Island (‘Ostrov’), which features Pyotr Mamonov in the role of a monk of the ‘holy fool’ tradition. The story is set in a religious community on a remote island outpost where the protagonist and his spiritual brothers live out the host-guest relationship of Symbol but with all the afflicted grains of that very threshold. And in this case I would say the whole film makes Gadamer’s point, but so do specific symbols inside the film (the island, a coal furnace, a bell tower, paints). Do you know this film?

Well, I have gone on far too long with my indulgence in these three themes of artistic knowing, the astonished imagination, and the character of symbol. Respond to whatever you like. But let me close by pressing you on two little related things I’ve been puzzling over in your Reclaiming Art.

Still from Pavel Lungin’s Ostrov (The Island)

First, periodically you support your points by way of Carl Jung’s philosophy of the archetypes of the collective unconscious. I can sense how there’s an appeal here insofar as Jung has a case for the ‘real’ that preserves a kind of ‘strange’ or ‘unfathomable’ at the heart of it all. Really Jung is saying that the order of things is a kind of artwork, the composition of which happens in the depths of our shared-psychic canvasses. But don’t you worry that Jung is still working with a highly conceptual—even positivistic—apparatus? And isn’t there something ironic in presuming to hold an explanatory view on what is swirling around in the unconscious? On p.130 you make a kind of capstone statement to so many of the points in the book—that great works of art “reconnect us with a reality too vast for the rational mind to comprehend”. But couldn’t one worry that Jung is in fact trying to do this sort of rational comprehension in his own peculiar way?

My other question is more of a clarification of something that might risk a misreading. In the ‘Art and Artifice’ chapter (especially pp. 32-33) you say that intellectual discourse can prove untenable over the long-term, and that the aesthetic administration of general judgments can be more effective in shaping the minds of mass society. I think you are critiquing manipulative strategies of such aesthetic practices, right? Are you agreeing that intellectual discourse is tricky and untenable, or are you just saying that ideologically-driven artists and leaders feel this way and so they incline to go with what they’re better at in terms of winning people over? In general throughout the book I hear you saying that the practice of discourse—of reason—really is vital (and the book is evidencing this, certainly), but that reason can fall into an over-estimation of its authority when it gets ‘too’ determinative, and that there is a kind of reason afoot in art that can remind philosophical reason of its own artistic roots. If I have that right, then when you critique artifice your point is, in a nutshell, that it is an insidious betrayal on both fronts?

J. F. Martel

J. F. Martel

The nuance you bring to the term “transcendent” is very important, I think. Art certainly does appear to be something we do in order to break through the conceptual overlays we project upon the world. In that sense, it is very much a way of accessing the “transcendent.” But this transcendent is not a fixed supernal absolute (though such a thing, as you note, may well be). It isn’t the world as such that this transcendent transcends, but only that semblance of world that the percipient believes himself to inhabit so far as the “superficial mediating structures” remain intact. In my normal, discursive mode of existence, an apple is just an apple, and one apple is more or less the same as any other. A very deeply ingrained (probably essential) mediating structure reduces each apple to a specimen, the instance of a type. But then Cézanne comes along and shows me that no apple is just an apple, that every apple is a singularity. For a moment, the mediating structure falls away. There is transcendence, but transcendence towards a “‘real’ that is more intrinsic to life than the machinations we are so often inclined to take as real,” as you put it.

Paul Cézanne, The Basket of Apples

I also agree that there is this other, transcendental thing that art does. Art reveals the affective forces that shape our doxa and ideologies, the forces that form the hidden facet of the aforementioned mediating structures. This is how I read Jung’s notion of the archetypes. The archetypes are not fixed and eternal, they don’t reside outside the world; they are rather like larger gears that tend to become occluded in the instantiation of their effects. Some of the forces that the archetypes represent may as well be eternal from a human standpoint because they are so vast, so cosmic, as to dwarf the human. But this doesn’t make them transcendent in an absolute sense; they remain immanent to what the world is and arise out of the immanence of that world. There is an important modification here of Jung’s archetypes, or at least of one reading of that concept to which Jung himself sometimes seems to subscribe, as you rightly point out when you mention his excessive rationalism. I prefer the more experimental and less assured Jung of the Red Book, for whom every instance of a symbol points not to a static, formal and rationalizable archetype, but rather to imaginal regions that are accessible only via such symbols because they lie outside the scope of our conscious knowing. Simply put, they belong to the nonhuman world, that other agency you mention, in concert with which we make our way.

This is why I love the passage from Mark Twain you cite and the paragraph on Jean-Luc Nancy. Both are hinting at a world that is in dialogue with us, a world that acts upon us even as we act upon it, such that our most humanized environments remain rooted in the nonhuman. There is a great moment in one of Thomas Ligotti’s short stories that gets to the heart of this: “Cozy little lobby you have here. But I’m afraid the atmosphere is doing strange things to that pot of ferns over there. Of course I know they’re artificial. Which only means Nature, one of the Great Chemists, made them at one remove, that’s all.”

Still from Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire

But what is even more interesting in what you write is this “more tacit knowledge,” this “felt relationship” that “humbles logical certainty” though it is responsible for the richness and complexity of actual, real experience. One idea that I’ve been trying to wrap my head around for a while now is that of an imaginal gnosis, an intuitive process that constitutes a kind of “knowing without knowledge.” Examples include the kind of cognition exhibited in the performance of Twain’s expert navigator, for sure. But isn’t this “gnosis” also what we see in the extremely complex and many-staged mating rituals or certain animals, the multigenerational migration routes of certain birds and insects, the phenomenon of dreams, and the creation of works of art? The opinions of evolutionary biologists notwithstanding, so much of what goes on in nature simply doesn’t make sense until we entertain the possibility of some kind of imagistic process, some kind of telos even, being at work at least in certain instantiations of what is called instinct. Be that as it may, I would love to know how this other form of knowing, co-creative with the world and “tacit” in the sense that it doesn’t require propositional language, relates to the concept of imagination you build in The Poetic Imagination in Heidegger and Schelling, where you seem to be arguing for an elusive though necessary power of thought in Nature that undergirds the rational scaffolding of philosophy. If that summary is even half right, then the connection with “the logic of the imagination” seems solid. Imaginative logic doesn’t reduce to common, anthropocentric rationality; rather, it enacts the logos of the world itself. It belongs to a thought of the cosmos—a nonhuman (though not necessarily anti-human) thought. It is to this nonhuman thought that I allude when I talk about “madness” or “lunacy” in Reclaiming Art. I am curious to know how you see that in relation to the concept of imagination you bring forth in your book.

The upshot for me is that everything we impute to culture is always-already present in Nature—in the world without humans (culture is Nature “at one remove,” as Ligotti says). There is a deeper agency; the world is always-already alive and does not need to be given life by a rational subject. Experience and perception, as William James and Henri Bergson argued, go all the way down. Art exposes us to this truth about the world, which is why I write in the book that it connects us with what Deleuze calls, with Cézanne, “the landscape before man.”

Where I differ with some of the current “nonhuman turn” thinkers who make a similar move is in their subsequent devaluation of humanity and subjectivity. That the world has agency doesn’t mean that humans have none. That the “object,” understood as process or event, is real and acts upon us, doesn’t meant that we as “subjects” have no place in the real—i.e., that we aren’t events in our own right. Rather, what it means is that the subject is already caught up in and entwined with the world, to the point of being inseparable from it. Subjectivity lies at the heart of the universe itself, not because the universe is the solipsistic experience of some quasi-divine consciousness, but because the universe can be described as either a constellation of objects or a swarm of subjects. The process philosophers were right to assert that subjectivity was one hundred percent relational, but I don’t think this implies that each subject cannot also have its own singularity, its own in-itself or “soul”—in fact that seems to be the very essence of what a subject is. The notion doesn’t make sense without it. What I understand to be my self may be impossible to disentangle from the physical, psychic, linguistic, mnemonic and historical nexus of forces that shape me as a being in the world; nonetheless, this self does not reduce to these forces, it isn’t a mere sum of these forces, not anymore than a video image is merely the sum of the pixels that make it up. In other words, maybe there is something singular about each human being (each human becoming) that makes her or him more than just a composite of traits or “bundle of qualities.” Perhaps one of the unique powers of the human mind is that it has enough logos to think the singularity that resides in everything else as well—in every animal, thing, or event.

You may or may not share my fondness for panpsychism. Nevertheless, I agree with you that our respective projects converge in this search for a way to articulate the fact that the sensible and intelligible each have an equal share in the real. There is, as you say, a ”mix of what the Greeks called mythos and logos,” and the “logic of the imagination” is a way of perceiving and appreciating this. Heraclitus for the win.

That brings me to your second point: the astonished imagination. As you do in your post, I’ve sometimes wondered how a Guggenheim/MOMA crowd might react to Reclaiming Art. You suspect I’d encounter “some head-scratching on this ‘truth,’ business, which you link up with radical beauty and even morality.” I think you’re right, because what you cogently gather up in this sentence are the Big Three to which modernity showed the door many centuries ago: the True, the Beautiful and the Good. To claim that these three terms point to realities as opposed to describing mere ideas that humans project upon the world is something of a heresy in the modern ethosphere. My sense, however, is that the “logic of imagination” can’t do without them, and I perceive these categories to be the real “pure forms of sensuous intuition,” at least insofar as human experience is concerned. (Isn’t it true that Kant’s philosophical claims in the three critiques rest on a deeper quest that motivates his entire project, a three-tiered quest which the critiques themselves perform—the first for truth, the second for the good, the third for beauty?) The True, the Good and the Beautiful are forms of imaginative consciousness as such; they are immanent products of the very structure of imagination, and therefore they motivate all imaginative activity. Maybe that’s why the modernist effort to break out of the prison of the beautiful only resulted in the discovery of new forms of beauty. There is this inversion of Plato, or at least of one iteration of Plato’s philosophy: what the modernists proved was that the category of “beautiful things” was not limited to those forms that exhibit the qualities the West has traditionally associated with beauty. The truly beautiful thing, in this immanent logic of the imagination, is not that which most closely approximates our preexisting notion of the beautiful; it is what affirms this notion while redefining it in a new light that gives it an entirely new meaning.

![Ridha Dhib, Deleuze : arc en ciel [via Flick, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]](https://wp.cosmos.media/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2018/04/Deleuze-arc-en-ciel_CC-BY-NC-ND-1024x768.jpg)

Ridha Dhib, Deleuze : arc en ciel [via Flick, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

It’s in that sense, I think, that art constitutes a “weird science,” a mode of knowing. The knowledge it imparts implies some unshakeable truths—three at least. Allowing ourselves to be affected by a great work of art, we remember:

- The truth of transcendence. The world is more than what we thought it was.

- The truth of what Deleuze called “transcendental empiricism.” There are deeper forces that shape the mediating structures we normally take to be the whole of reality.

- That, in the light of 1 and 2, the real reveals its own intrinsic mysteriousness; art communicates the truth of radical mystery.

The radical mystery of the real isn’t just an impression I get, a kind of hallucination that art induces within me. Radical mystery describes the world as a matter of fact. To affirm it is to make a positive claim about the nature of reality. All of our claims about the world are contingent upon a deeper creative indeterminacy that is intrinsic to the world as such. To put it differently, the mystery of being is not a riddle I just haven’t yet found the answer to; it is the way being is. Paradoxically, my realization that I will never know the real in its inmost is itself a direct knowing of the real as such. This, I believe, is the truth that art reveals to us through all its world-disclosures.

It’s on this base, this conviction that radical mystery has positive value (that the strangeness is ontological rather than merely epistemological) that I tried to work out my ideas about art and artifice. “Artifice” describes the use of aesthetic form to deny the truth of radical mystery, to make it seem as though the world can and has been figured out, i.e. that the world is eminently knowable, such that we are in a legitimate position to judge it. In this sense, artifice is metaphysically false even if its content might otherwise be good or true or useful. By contrast, “art” describes the use of aesthetic form to affirm radical mystery, to remind us that the world can never be totally figured out, that it is immanently unknowable (and that this can, paradoxically, be known).

Still from Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker

You summarize the argument as follows: “Affectivity intuitively wants a shot at the Imaginal, but artifice steps in to curate the show and feed us a steady supply of doxa that we, ironically, cling to and upgrade and download as little badges of our own perceptual savvy.” That’s it: artifice tells us that what we perceive is the whole of a phenomenon. It therefore allows us to judge and claim to know the world, since it has reduced all of reality to what Shakespeare called our “little world of man.” Economically and politically speaking, artifice serves to surreptitiously validate and underwrite a state of affairs (for example, the modern neoliberal state), making it seem like a self-evident fact of nature instead of the contingent accident that it is in truth. Instead of disclosing infinite possibility, it closes off possibilities. Art, on the other hand, is always affirming infinite possibility by showing us how even our most cherished beliefs about the world are themselves affective forces coursing through the world—forces among forces. That art involves a kind of “madness,” or at least something that the status quo might perceive to be “mad,” inevitably follows from this. The affirmation that even the things that look most solid and unchangeable are in truth contingent—this is threatening to the rational order that any self-respecting episteme will strive to maintain and absolutize. It is an affront not to reason itself but to the cult of rationality that would place reason above that other mode of knowing, and it is an affront because it shows us that the world does not exhaust itself in ratio. At the same time, this “madness” doesn’t completely negate reason or logos itself; it is itself a voice of the logos as logic of the imagination. So there is an affirmation of reason here, but reason without anthropocentric judgement. Your insights into the work of Caspar David Friedrich, which you weave into a brilliant discussion of the symbol to which I can’t think of anything to add, is helpful here:

- “Human existence is a journey grounded in some kind of direction-pulled contemplation.”

- “We aren’t the center of this existence in some authoritative way.”

- “The center or what we’ve been calling the order of things consists in an ever-unfolding play between our journey and a hovering expression of a reticent but resilient beauty of truth for which we intuitively long and sometimes feel in a radix kind of way.”

Right on! That the human journey has its place in the world at all means that we are welcome here—we are at home in the cosmos by virtue of the fact that we participate in it, that we are part of it. We find ourselves thrown in this big weird place, but we have the words and the means to ask for directions. And when we muster the courage to ask, we can receive information, we can enter into a relation of trust with our environment and its denizens. So your scenario of asking directions in a foreign place is a nice analogy for what is going on in art. To create (and experience) art is a way to ask nature for directions, to enter into a dialogue with it in order to know the “right paths.” The directions aren’t given to us in our native language but in the language of symbols. They are necessarily cryptic because nature itself is ambiguous, indeterminate, and creative. Interpretation, a kind of scrying, is always in order. Humans are at home in the world, but our home is a garden of forking paths, in Borges’ words. If it’s a house, it isn’t a cozy suburban bungalow but a sprawling, haunted mansion, kind of like the everchanging house in John Crowley’s fantastic novel Little, Big (or in Kubrick’s The Shining, for that matter). A single set of directions won’t do; we must keep asking, we must keep the conversation going, in order to avoid feeling too at home and losing our way.

Still from Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker

That may be the beginning of an answer to your final question concerning the value of intellectual discourse. I really like the answer you propose to that question. My true feeling is that I would rather live in a world where artifice did not exist at all, and where the minds of mass society could be shaped solely through rational discourse. For this rational discourse not to run amok, however, it would have to be tempered by a constant awareness of the fact that rationality always gives us a partial view of things; that the light of reason is more like a flashlight we wield than a sun that illumines everything. Art provides just such an awareness by restoring our rational judgements to the imaginal (meaning preconceptual and affective) plane from which they arise. This imaginal plane is not irrational so much as supra-rational—it works on that imaginal logic from which common reason is derived (as you write: “there is a kind of reason afoot in art that can remind philosophical reason of its own artistic roots.”). If artifice can rightly be called a “betrayal,” it is only because it is incorrigibly inadequate to the real. That said, I am not enough of a romantic to believe that we could do without it. Insidious though it may be from a metaphysical or spiritual standpoint, artifice may well be indispensable in any real world situation where things get practical. What I mean is that it may be too much to ask of a human collective that it avoid artifice altogether in its promulgation of values and its effort to maintain itself. Which is fine, I think, because we can live with artifice (we always have). What we can’t do is live without art—without that crack that lets us peer outside the dome of our artificial mediating structures. If artifice has become pernicious today, it’s because technology has made it ubiquitous. People need real art to act as a countermeasure, subverting it at every turn.

I’ve gone on way too long, but would like to steer this back to your essay, “Phenomenological Aesthetic of Cinematic ‘Worlds’,” with a few remarks. Your argument is that film’s “ontological possibilities” reside in world-disclosure. What I am trying to do above and in my book is to work out certain implications of this process. The question is: what does world-disclosure as such tell us about the nature of reality? You end your paper by claiming, in keeping with your profound insights on Heidegger and Schelling, that “by orienting our aesthetic to the phenomenon of world-disclosure,” philosophers might achieve an accomplishment similar to that accomplishment of cinema as an art form. This seems to underwrite the idea that “philosophical reason” has “artistic roots.” There is, in your work, a call to poiesis in philosophy. But what form do you think a poetic philosophy would take? Do you believe philosophy is at bottom a kind of artistic enterprise (as I may have implied in imputing Kant’s critiques to an affective quest underlying his conceptualizations), or would you argue for some necessary bifurcation of art and philosophy?

Christopher Yates

Christopher Yates

Terrific thoughts that lend a fitting capstone to so much of what we’ve been discussing. Three points in particular stand out to me. First, you reiterate so well how we all often tend to overlook the real-time nature of the mediating structures of perception, and thus think too comfortably according to the reductive frames of ‘semblance’ rather than ‘singularity’. Second, your readings of Jung and Jesus (hitherto unlikely companions) underscore your emphasis on the way that the landscape of ‘immanence’ is rich with ongoing possibilities that are not at the mercy of a distanced ‘absolute’ authorship nor under the thumb of some nihilistic finitude. Third, I like your recovery of the True, Beautiful, and Good as “immanent products of the very structure of imagination” and thus intrinsic and life-giving reference points for the activities of art and thought alike. Maybe we could connect this idea to your later one about the way radical mystery is there in the very nature of reality, such that the logic of the imagination engages with the ontological strangeness by way of those very ‘transcendentals’?

You also mention your curiosity about ‘imaginal gnosis’. I’m not very up to speed with this, but I do sense a connection to the early twentieth century philosopher, Henri Bergson, whom you note, and his embrace of Intuition as a praxis of thinking. (Bergson, as you probably know, was really important for Deleuze). Let’s admit that how ‘gnosis’ and ‘intuition’ can play out is tough to pin down, and that they are disarming notions because they tend to protest against our default formulas for determining ‘playings-out’ in general. Still, Bergson says that intuition is a capacity we have to, so to speak, reboot in order to situate ourselves and our ideas afresh back in the creative durational becoming that is at the heart of life and nature. He says the ‘intellect’ has become too authoritative as the measure and mode of what you and I have been calling ‘ratio.’ The intellect isn’t ‘bad’ per se, but it tends to exercise too much confidence in practicing ‘understanding’ by way of cutting things up and sussing out the apparent causal chains at the heart of the real. We need a better balance. It’s interesting that when Bergson tries to characterize what intuition looks like he frequently draws analogies to artistic process and perception (I think this is a page he borrows from Schelling). Now, I think it’s okay if we stay imprecise with what we mean by ‘imaginal gnosis’ and ‘intuition.’ If they don’t lend themselves to formulas they do issue a special charge to us: surrender some habits of thinking and living, including the implicit adherence we hold to simulacra-driven ontologies and epistemologies. The charge is to enter into a practice of restraint more than a path of conquest. The mystical tradition called this Gelassenheit, which centers on a practice of ‘letting.’ To ‘let’ means to let something (say, an object or idea we want to understand or concretize) show itself amid the nexus of how we are relating to it. That’s a ballast against utilitarianism in our lived-experience or intellectualizing. If we work on this then a ‘wakefulness’ and ‘watchfulness’ can ensue. I can’t elaborate but I’ll just say that I think Leonard Cohen (the music, the poetry, the spiritual practice, the faith in resilient-if-reticent-Meaning) is a model in this regard.

Still from Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life

Maybe I can take this thought as a bridge to your closing question to me about the extent to which philosophy is an artistic enterprise and/or something nevertheless distinct from art. Here I will resist the silly idea, which we sometimes hear, that philosophy is a form of ‘conceptual art.’ Instead, I would say that where this orientation of letting—waking—watching by means of imaginal intuition is at work, philosophy and art spring from the same root (much like, for Kant, ‘understanding’ and ‘sensibility’ spring from the same root: imagination). Both practices ‘say’ things according to some devotion to the kind of concentration that asks questions past the point where questioning usually stops, and when we say things in this way we are trying to involve ourselves (again, ontologically and epistemologically) in what Gadamer calls the ‘excess of meaning’ that ‘must be integrated into the self-understanding of each person.’ Everyone and every thing ‘says’ something in the sense that the world is rife with symbols and with the ache they evidence to carry the chorus of meaning. But philosophy is like art (including the visual narratives of cinema) in terms of wanting to ‘speak’ well, and in both cases this first of all requires the imagination as a way to recalibrate the voice—to speak more carefully than what Kierkegaard called ‘chatter’ and to concentrate better than what befalls perception in the realm of artifice.

Philosophy’s affinity for ‘ratio’ (‘measure-taking’, as I hear it) may make it seem like it practices a whole different voice than art. But we have to remember that at the ground floor of every metaphysical inquiry, syllogistic exercise, or academic lecture is an aesthetic hunch—a ‘sense of’ or ‘feel for’ or ‘picturing of’ the mysterious excess of meaning that draws our curiosity—sometimes insatiably—toward a purposeful concentration. Philosophers have to first of all imagine that the hunch they feel for a question’s decisive importance is worth trusting, or at least trying. Such is the nature of curiosity, and isn’t curiosity the precise ‘letting’ that art performs? Both philosophy and art are forms of creative ‘making’, and both are also vulnerable to the perilous temptations to be too ‘willful’ and dogmatic in their productions.

That said, I do think there’s a bifurcating practice between philosophy and art that ‘can’ be practical and good. Both practices have their traditions and both have their mediums, and students of both should have an operating knowledge of the terrain they are working in. It can be a grace to work within a tradition of tools and techniques, and the ‘singularity’ of these shouldn’t be mushed together. So I’m saying that philosophy and art are born in the same vocation of the human imagination and inspired by the same aesthetic relationship to the mystery at the heart of the real, but that doesn’t mean every artist has to learn formal philosophy or every philosopher has to direct films. Now and then one meets a person who does both, and that is a truly remarkable thing. My students are like this and you are certainly this way—I’m jealous.

Well, this has been fun. Thanks for hearing me out and waking me up to hopeful hunches of discernment. Onward!

J. F. Martel

J. F. Martel

I love the concept of Gelassenheit and couldn’t agree more about Leonard Cohen as an exemplar of this magic of “letting.” Let the river answer.

It’s been a real pleasure discussing all this with you, Chris. Thanks for the intellectual generosity you’ve shown this journeyman.